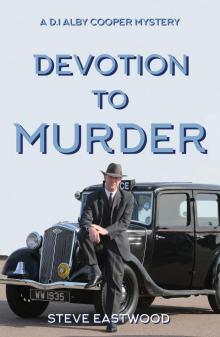

- Home

- Steve Eastwood

Devotion to Murder Page 2

Devotion to Murder Read online

Page 2

‘Yes, of course, my dear.’

‘I must do some washing and ironing. It’s starting to pile up. We will have no clothes to wear if I don’t. You will be all right here on your own?’

‘I will be fine, but, before you go, it would help me if you were to give me your special treatment. It would help me relax, you know.’

‘I am happy to try, my lord. If you think that it will help.’

‘Yes, I really think it might.’

Adina sat on the side of the bed and pulled back the covers. She then went about her business with skill and dexterity. It did not take long before she relieved his tension. Jeremy soon went off to asleep.

Adina left his lordship’s bedroom and she walked to her apartment at the other end of the building. She came back to his lordship’s room, for ten minutes or so, at around 4.00pm, and, although Adina was reluctant to wake him, she needed to give him his medicine. He soon dropped off again.

About 4.30pm Jeremy was woken from his slumber by the sound of shouting, which appeared to be coming from outside in the garden. He couldn’t tell whether the voice, or voices, were male or female, but on recalling that Stephen Savage, the gardener, was carrying out some work in the immediate area, he reassured himself that the noise was due to Savage’s efforts, and, not feeling inclined to go to the window to investigate the matter, he stayed in his bed. The noise didn’t appear to go on for very long and he had soon dismissed it from his mind. Jeremy continued with his newspaper, and, after a short while, he managed to drift off to sleep again.

*

Just after 6.00pm, James left the kitchen to take some slops out to the bin area. As he got to a point near to the bins, he cast his gaze over to the summerhouse, which was some fifty yards away across the lawn, to his right. What he saw threw him totally. Sister Margaret was lying prostrate on the grass.

‘Sister! Are you all right?’

She gave no response as she was rolling on the ground in front of the summerhouse. James realised that something was amiss, so he ran across to investigate, and gasped in horror when he approached her and saw that the nun’s wimple was lying on the floor beside her and she was bleeding heavily from a head wound. She was staring at James, almost beseeching him to end her misery. Her lips were moving as if to speak, but James could hear no words. Very soon, he realised that she was still.

He was stunned rigid and wanted to do something to help, but he didn’t dare touch her. She was a woman after all. The lad suddenly felt very exposed and vulnerable. He left the sister where she lay and ran back to the kitchen to fetch Mrs Aldis, but she was nowhere to be found. He began to panic. What if people think it was me? James ran through the house and started shouting ‘Help! Help!’ at the top of his voice. Finally, he found Jenkins, who was in the dining room. ‘Mr Jenkins. Come quick. I think the nun’s dead! Will you come outside with me and have a look, please?’

‘What do you mean, she’s dead? If this is your idea of a joke, young man, then it’s in very poor taste!’

Beryl then stepped into the room, having been attracted by the sound of James’ shouting. The two men rushed outside and without having any notion as to what the fuss was about, she followed on behind them. They found Sister Margaret lying on her side in something akin to the recovery position. Raymond Jenkins bent over her and gently tapped her face, almost as if he was trying to wake her from her slumber. ‘Sister, Sister. Come on, up you get.’

The nun made no response to his pleading, and, in view of the extent of her wounds, Jenkins realised that she was unlikely to do so.

‘Her cross has gone. It was definitely around her neck when I saw her earlier on,’ observed James.

‘She might be lying on top of it,’ said Jenkins.

Beryl took control of the situation. ‘Never mind the bloody crucifix! Ray, go and call for the doctor and then call the police!’

Jenkins rushed away to the house to use the phone in the study. While James stood watching, Beryl tried to resuscitate the sister using the limited training that she had received a long time before as an auxiliary nurse. She knelt across the nun, and, for what seemed like five minutes, she pumped her chest and checked for a pulse. But, Beryl’s heroic efforts were to no avail: Sister Margaret was gone and there was nothing she could do to bring her back.

After about fifteen minutes, an ambulance arrived on the scene. The crew were soon joined by the local GP, Doctor Graham Stevenson, who examined the unfortunate lady, but he reached the same sad conclusion.

Sister Margaret was dead. She had gone to meet the boss.

*

Jesus Christ, I’m shaking. But I’ve never felt so alive. Stupid, evil bitch. How dare she say that the war was God’s way of keeping the population down? Didn’t she understand that we all lost family? She probably never had any family of her own, and she certainly won’t be having any now. I know I probably went too far, but at least it will stop her from spreading her poison. No regrets. The bitch deserved it.

*

Lord Roding was woken by Jenkins, who was tugging at the sleeve of his pyjamas.

‘My lord. Wake up, please. I’m sorry to disturb you, but there has been a serious incident in the grounds.’

‘What kind of incident, Jenkins? I’ve only just managed to get to sleep, damn your eyes!’

‘Sister Margaret has been murdered!’

At this news, Jeremy sat bolt upright in his bed. ‘She’s been what?’

‘Murdered.’

Jenkins went to the window and he drew back the curtains to allow some light into the bedroom. He continued to speak as he did so. ‘The nun, Sister Margaret. Young James found her about a half hour ago; she was lying on the floor outside the summerhouse. She had wounds to her head and to her neck, and there’s blood everywhere. It looks like someone has beaten her to death with a garden spade.’

‘Who? Who has beaten her to death? Did Savage see what happened to her? He was out there this afternoon, I’m sure he was. I heard him out there earlier on.’ The shock overrode the tears he might have had.

‘I have not seen Savage since early this morning, my lord.’

‘Has someone called an ambulance or a doctor?’

‘Yes, my lord. The ambulance is here, and Doctor Stevenson is with Sister Margaret as we speak. I also called the police, but they haven’t arrived yet.’

‘What about young James. Is he all right?’

‘Yes, my lord. Just a little shaken up, but he’ll be fine.’

‘I need a cigarette, Jenkins. Light one for me, will you?’

‘Is that wise, my lord? The doctor was very firm on the point that you shouldn’t smoke,’ pleaded Jenkins.

‘Don’t argue man. Just get me one, will you?’

The butler did his master’s bidding; retrieving a packet of cigarettes from the inside pocket of his tailcoat, he lit a Park Drive and handed it to Jeremy, who took a long and satisfying drag.

‘That’s better.’

Jenkins helped Jeremy into his tweeds and he selected a shirt from the wardrobe. After finding some footwear, he sat him in his wheelchair.

‘Right, Raymond, let’s go and see what is happening outside, shall we?’

They left the bedroom.

Once downstairs, Jenkins wheeled his lordship to the study, parking him next to the french doors providing access to the garden. He would, from this point, be able to monitor events without becoming embroiled in what was happening around the body.

Jeremy could see that the cook was standing talking to the doctor. She had an earnest expression on her face. Jenkins had told his lordship of her desperate efforts to save the sister. The poor woman looked devastated, and he could see that her apron was covered in blood. He admired her and felt sorry for her in equal measure. His lordship instructed the butler to call the doctor over to him, in order that he might enquire as to

Sister Margaret’s present condition and seek his opinion as to what might have caused her death. As the master of the house, he wanted to hear the facts from Stevenson for himself.

After hearing the doctor’s account, Jeremy was overcome with grief, and, seeing his master’s distress, Jenkins took him back to his bedroom so that he could rest and regain his composure.

About ten minutes later, Police Constable (PC) Alfred Lewis, the village constable, sped onto the scene by bicycle. He looked for all the world like Fatty Arbuckle in a cinematic trailer for The Keystone Cops. As he entered the garden, he dismounted from his machine with such haste that he very nearly plunged into a nearby flowerbed. He was beetroot red in the face and fighting for breath.

‘Sorry I’m late, but I was at the other end of my beat when my wife got word to me about this incident.’

At once, Doctor Stevenson outlined the situation to the officer and the sequence of events as far as he understood them. He showed PC Lewis to the body, gave him an explanation of his findings and, having earlier been badgered by James, he told the constable about the missing crucifix. The doctor stood over the body and explained his conclusions as to the cause of death.

‘Sadly, Officer, the lady is deceased. She most likely succumbed to the wounds sustained to her head and neck, although we will not know for sure until a post mortem has been carried out. In my opinion, it is a clear case of unlawful killing, so I would advise you to leave the body where it lies and protect the scene of the crime from any interference. I think we must inform the coroner about this one.’

The doctor pointed to a garden spade that was lying on the floor of the porchway to the summerhouse. ‘There’s your weapon, I would suggest.’

‘Doctor, would you mind remaining with the body just while I telephone the CID [Criminal Investigation Department] and the rest of the cavalry.’

The doctor agreed, and PC Lewis went off to the house to find a telephone. As he got to the kitchen door, he was met by Jenkins and the constable told him he should assemble all members of staff in the kitchen, where he wished them to remain. This was apart from Mrs Aldis. PC Lewis explained that, due to the amount of blood on her apron, she should remain in the dining room to prevent blood transferring from her garments to those of other staff. Lewis escorted her to the dining room, where she removed her apron and sat down. He then went to use the telephone.

On his return to the garden, he found the doctor seated at a table completing some notes of his own. As Lewis approached him, the doctor remarked, ‘I just need to go to my surgery to collect something. I will be back in about ten minutes, if anybody wants me.’

About 7.20pm, PC Lewis was still standing guard over the body when he was joined by Detective Inspector (DI) Albert Cooper and Detective Sergeant (DS) Brian Pratt of the Essex Constabulary. They had been met at the front door by Jenkins, who had directed them towards the murder scene. Doctor Stevenson had just returned from his surgery. Introductions were unnecessary as he was known to both detectives.

‘Intriguing one this, young Cooper,’ said the doctor.

‘What are we dealing with here then, Doc?’

‘Looks very much like a murder to me. Someone gave her a few hefty whacks with that, I would imagine.’ The doctor indicated the spade, which was still in position on the floor. He continued, ‘Anyway, that’s for you and the pathologist to confirm, Alby. Obviously, I’m not at liberty to issue a death certificate at this stage, and I’ll have to report it to the coroner.’

He indicated the victim’s wounds, which consisted of deep lacerations to her head and neck, and the wimple that remained on the floor next to the body.

‘I am given to understand the lady’s religious name is Sister Margaret, and that, by all accounts, she was not all sweetness and light. In due course, the coroner will need her birth name. Still, I expect the diocese will be able to provide you with that.’

Albert Cooper had served with the constabulary both before and since the war. He enjoyed the sobriquet of “Alby”, which had been given to him by school friends. He was a large man of thirty-six years of age. He stood six feet three inches in his stockinged feet and was of a strong, lithe build. He had a full head of black hair, which was neatly cut in a “short back and sides” and smoothed with Brylcreem. Alby was quite a handsome individual with a strong chin, although he did have a boxer’s nose, which was a souvenir from his army days.

Cooper’s “bagman”, Brian Pratt was thirty-five years of age. He was slightly shorter at five feet eleven inches tall, and of a thin build. In terms of physical stature, he was a shadow of his boss. Unfortunately for Pratt, he had inherited the balding gene. What was left of his hair was blond, as were his eyebrows and moustache.

Whatever their shortcomings were in the looks department, Cooper and Pratt were regarded by their colleagues as thorough and capable detectives.

Alby Cooper knew his ground and the people on it. At the outbreak of hostilities, he had been a serving officer in the Colchester Borough Constabulary as well as an army reservist. He was one of the first to be conscripted into the army, serving with the 12th Lancers as a part of the British Expeditionary Force.

At Dunkirk, he was captured, and he spent the next four years as a guest of the Germans. Those years had taught him a lot about human nature. When he was finally released, he was a shadow of his former self and he was left with scars, not all of which were physical. At the outbreak of war, he had had a girlfriend, Jennifer, to whom he had been engaged to be married. Unfortunately, she had tired of waiting for him and she had become involved with an American airman, whom she married in quick time. She now lived with her husband in Arkansas. Cooper’s trust in women was severely damaged by this experience and he had become embittered.

Cooper rejoined the police force after the war had ended. He channelled his bitterness into sheer hard graft and a dogged approach to investigations, allowing himself little time for a private life. As a result, he had rapidly risen to the rank of detective inspector. He was now faced with a murder and he was determined to get a result.

*

Cooper and Pratt were standing in the rear garden of Beaumont Hall, surveying the scene; the sun was fast disappearing below the horizon, Doctor Stevenson had departed, and they had been joined by Brendan Withers, a forensic scientist.

A dead nun lay before them.

‘It definitely looks as though the weapon was the spade. We shall have to take care to bag it and keep it clear of the body. Then, later, at the lab, the blood on the spade will be compared with that of the victim. The pathologist will also do a physical comparison of the spade against the wounds during the post mortem,’ said Withers. ‘Do we know the origin of the spade, sir?’

‘Yes, Brendan. Apparently, it was left in the ground over there earlier this afternoon by the gardener, a Mr Savage.’ Cooper pointed to what looked like a large half-dug flowerbed adjacent to the summerhouse.

‘What does his lordship say about all of this?’ said Withers.

‘He’s deeply shocked. In fact, he’s taken to his bed. Seems to be one tragedy after another with his family, and now this. His lordship appears to have been quite fond of the woman; she was something of a companion for him. We’ll have to arrange to take a witness statement from him when he’s settled down a bit.’

Cooper pointed towards the deceased and gave Withers an instruction, ‘Brendan, I want you to supervise the removal of the body from the scene to the mortuary, and arrange for someone to travel with it, so that they can prove continuity.’

‘Yes, sir,’ said Withers. ‘I will keep you informed of the time and date of the post mortem. I imagine that you’ll want to be there, won’t you?’

‘Yes, I will. Thanks Brendan.’

‘Brian, we’ll also need Brendan and his team to carry out a careful search of her bedroom in the house, but, for now, will you just make sure that it’s locked, an

d that an officer is stationed outside the door.’

Cooper called across to Sergeant Scott, a uniformed patrol sergeant, who was lurking on the periphery of the scene.

‘Sarge, I need you to cordon off an area, say, a fifty-yard circumference of the scene, and post the most confident member of your section to act as gatekeeper. They’ll need to have the wherewithal to be able to stop people entering the cordon who have no business being there. That might even include the chief constable, or any other senior officer who happens to be curious or just want to put their snout in.’

‘I think we can manage that, governor. I’ve got a few smart alecs on my section who could cover it.’

‘Well, whoever you designate, they’ll need to keep a log and they must be able to stand their ground. In the meantime, the forensic team will be busy within the cordon, but I want the security of the cordon maintained even after the body has been taken away.’

‘Leave it with me, governor.’

‘We should also organise a search of the grounds, so we must call some extra bods in to help with that. May I leave it with you to organise?’

‘Will do, governor. It’ll be getting dark shortly though.’

‘Do what you can, Rob. If you need to carry on in the morning, then so be it.’

‘But what are we searching for?’

‘Any other weapons, blood, a possible exit route indicated in the long grass or footprints; that kind of thing.’

‘Brian!’ shouted Cooper, calling Pratt across to him again.

‘Brian, I need you to get somebody to speak to the school caretaker to ask him if we can set up our incident room in the school. The kids are on holiday for a few weeks, so it should be OK. Any argument, come back to me and I’ll have a word with the headmistress. I’m off to speak to the boss to update him and ask for some more staff. For now, I’ll leave you, Rob Scott and his section to supervise the scene.’

Cooper climbed into his Wolseley and drove the six miles to the town hall where the office of the superintendent of the Colchester Division was located. It was mid-evening. He realised that he was being somewhat optimistic given that he was already aware the superintendent was due to attend an evening council reception. He thought there might just be a chance that he could get a message passed to him.

Devotion to Murder

Devotion to Murder An Oik's Progress

An Oik's Progress