- Home

- Steve Eastwood

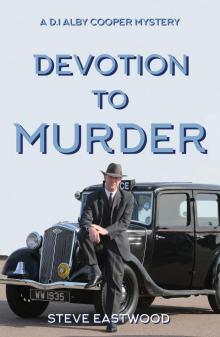

Devotion to Murder

Devotion to Murder Read online

Devotion

to

Murder

Steve Eastwood

Copyright © 2018 Steve Eastwood

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of research or private study, or criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, this publication may only be reproduced, stored or transmitted, in any form or by any means, with the prior permission in writing of the publishers, or in the case of reprographic reproduction in accordance with the terms of licences issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside those terms should be sent to the publishers.

Matador

9 Priory Business Park,

Wistow Road, Kibworth Beauchamp,

Leicestershire. LE8 0RX

Tel: 0116 279 2299

Email: [email protected]

Web: www.troubador.co.uk/matador

Twitter: @matadorbooks

ISBN 9781789013450

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Matador is an imprint of Troubador Publishing Ltd

Contents

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

PROLOGUE

DAY ONE

DAY TWO

DAY THREE

DAY FOUR

DAY FIVE

DAY SIX

DAY SEVEN

DAY EIGHT

DAY NINE

DAY TEN

DAY ELEVEN

DAY TWELVE

DAY THIRTEEN

DAY FOURTEEN

DAY FIFTEEN

DAY SIXTEEN

DAY SEVENTEEN

DAY EIGHTEEN

DAY NINETEEN

DAY TWENTY

DAY TWENTY-ONE

DAY TWENTY-TWO

DAY TWENTY-THREE

DAY TWENTY-FOUR

DAY TWENTY-FIVE

DAY TWENTY-SIX

DAY TWENTY-SEVEN

DAY TWENTY-EIGHT

DAY TWENTY-NINE

DAY THIRTY-ONE

EPILOGUE

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to offer my grateful thanks to those who gave so generously of their time, expertise and advice during my research and the writing of Devotion to Murder. In particular, I’d like to express my gratitude to my old friend Tony Oswick, a talented writer in his own right, and David Evans, who is an award-winning crime writer. Their unstinting support and guidance gave me the confidence to keep working towards a, hopefully enjoyable, product. I would also like to thank my friends, Adina and Ray Titchmarsh, Steve Savage, Martin Chipchase, Jeremy John (Lord Roding), Sue Jacobson (Lady Fanny), and my son, James Eastwood, all of whom were players in my Murder Mystery group and provided the inspiration for the tale.

Finally, I would like to thank my friends; Brian Prater, 1940s enthusiast who lives the lifestyle and appears with his Wolsley on the cover; and Robert Wong, a highly talented professional photographer who took the images and has kindly given his permission for them to be used.

Steve Eastwood

Clacton-on-Sea

2018

PROLOGUE

It was July in the year of our Lord 1949. After six years of conflict, most of Europe had settled down to something akin to peace and normality. There were still international tensions, of course, but these were of no real interest to the inhabitants of Beaumont, a small village on the Essex coast. For many of these people, life had already altered fundamentally. Having to come to terms with the loss of loved ones, scraping a living and food rationing, they were doing their best to shake off the effects of the war. There was some optimism, for those who could find it within themselves, but there was hardly a spirit of forgive and forget. It was against this background that Sister Margaret, a Carmelite nun, arrived in the village. She had been sent on a mission by the Vatican to help the lord of the manor in his conversion to Catholicism. Jeremy John Beaumont, the 7th Lord of Roding had been a devout Christian, but his faith was shattered when his first wife, Bettina, was killed during an air raid, and again when Edward, his only son and heir, later died in a road accident. Desperate to find solace, Jeremy had remarried in haste, to Francine, a woman who was twenty-six years his junior. She soon tired of the marriage, and, when Jeremy became ill, they began to live virtually separate lives. It was to be Sister Margaret’s mission to guide Jeremy back to the path.

As for the indigenous population of Beaumont, they were not big on Catholicism or religion of any stripe. So, when they saw her about the village, they found her something of an oddity. In their eyes, she was, at best, an anachronism, but some of the people resented her presence deeply. Their reasoning was simple. If God is love and Jesus really exists, then, surely, they would not have suffered for the past ten years and would still have the loved ones who had been so cruelly taken from them. How, then, did this “Bride of Christ” have the nerve to show her face in their village? As if this were not enough, she was living it up at Beaumont Hall with his lordship, if you please!

1

DAY ONE

Tuesday 12th July 1949

‘Do try to relax, Jeremy,’ said the nun. ‘Sometimes the Lord God makes us ill to test our faith.’

‘Well, if that is true, I wish he wouldn’t test me quite so rigorously, Sister.’

The nun crossed herself, as a precaution.

Lord Jeremy Roding was propped up in his four-poster bed, surrounded by books and newspapers. Sitting alongside him was Sister Margaret. A tall, attractive and elegant woman, whom his lordship estimated to be in her late twenties. He observed her as he lay on top of the eiderdown, and he imagined that, confined beneath the shapeless habit, there had to be a healthy libido the young nun was fighting to control. However, he was no longer in any condition to put his theory to the test. Had she come into his life twenty years ago, well, things would have been very different indeed. He would have done his best to tempt her and satisfy his curiosity. But, for now, as he was a deeply troubled man, she was trying to comfort him by quoting from the scriptures. It wasn’t really working, so he tried to divert her from her efforts.

‘Anyway, my dear, how are things with you?’

‘Good, Jeremy, but, I have found that the people in the village don’t like me very much. Probably because I am a foreigner.’

‘You must forgive them, Sister. They have been through a lot in recent years. They are very suspicious of strangers in general, let alone foreigners,’ his lordship chuckled to himself. ‘I firmly believe that one has to have been born and bred in the village to ever be accepted at all. They are a funny lot, really.’

His lordship bent forward, and his laughter turned into a fit of phlegm-laden coughing. The nun got to her feet, turned and reached across to pick up a jug from the dressing table. She poured a glass of water and handed it to him. He accepted it and drank it down greedily.He continued, ‘No you mustn’t let them worry you.’

At the age of sixty, Jeremy was suffering from a respiratory illness that had left him relying on full-time nursing care. Although not totally bedridden, he was quite immobile, and reliant on sticks and a wheelchair to get himself around. Once a powerful and charismatic individual, his shock of red hair and beard were still as thick and lustrous as ever, but he was greying, and, with his lack of mobility, he had put on another three stones in weight.

‘So, Jeremy, where is the Lady Fanny today?’

‘Fanny has gone up to our Londo

n house for a few days.’

‘She goes there a lot, does she not?’

‘Yes. She spends much of her time up there pursuing her business interests. The art gallery, exhibitions and whatnot. She is very ambitious, you see, and she does have her own network of friends in London. She finds life here, at Beaumont, rather tedious, I’m afraid. One would definitely say that she is her own woman.’

‘I often wonder why you call her Fanny and not by her real name, Francine. I think it is a very pretty name?’

‘Well, she doesn’t like it for some reason. And, it seems, all her friends call her Fanny. It sums her up totally, I think,’ said Jeremy with a hint of bitterness.

The nun did not understand the reference and was unable to comment. She just nodded and gave a smile.

‘Anyway, Jeremy, I think you need to get some rest. I am going to go into the garden for a while to do some more of my painting.’

‘Right you are, my dear. Try to create a masterpiece for me, will you?’

She got to her feet and helped him get under the covers, then left the room, closing the door quietly behind her.

In despair, his lordship picked up a newspaper and tried to read in the hope that this would have a soporific effect. He was bored and had tried hard to get off to sleep. In fact, he had tried too hard and it was working against him. Jeremy was now staring at the ceiling, pondering over the remaining years of his life and what they could possibly hold for him. He was in quite a philosophical frame of mind and he told himself that, compared to other people, he had no real reason to complain. There were always plenty of staff about the place, so he was not exactly alone at Beaumont Hall. He had a reliable butler, cook, and gardener, and there were one or two youngsters working on the estate. No, there were many people considerably worse off than him.

But it was a sad fact that Jeremy had begun to prepare for the end of his life and he was in receipt of spiritual counselling, which was being provided by the fair Sister Margaret. She had already been staying at Beaumont Hall for a couple of months and he had found her to be a source of great comfort.

It was also quite fortuitous that, when Jeremy had fallen ill, he had managed to engage the services of a full-time nurse in the person of Adina, the wife of his butler, Raymond Jenkins. She was already living at the Hall and had been at something of a loose end. She had been trained as a nurse, and, after the war, she had served in Vienna with the Red Cross, which had led to her meeting her husband Raymond, who was serving there with the British Mission.

Jeremy had warmed to Adina and found that she was ideal for the job. She was very attentive, thoughtful and she cared for all his physical needs. She had a lively sense of humour and was charming company. She was also damned attractive.

*

‘You are late again, young man,’ shouted Beryl Aldis, ‘by fifteen minutes, and that’s the third time this week. I shall be having words with Mr Jenkins about you, unless you buck your ideas up.’

‘I’m sorry about that, Mrs Aldis. My mate Alfie and I got into a shoal of roach, and they just kept coming and coming. I suppose I just lost track of time.’

‘You’re lucky to have this job you know. There’s them who fought in the war and came back to nothing. Just you keep your eye on the time in future.’

Beryl Aldis was a matronly figure and, as the cook, she ruled the kitchen area with a rod of iron. She had been employed at Beaumont Hall for most of her adult life and knew the workings of the place, inside out. Compared to the years before the war, they now operated with a relatively small number of staff. Beryl knew that discipline had to be strictly maintained, if the household was to function at all efficiently.

James Davidson was kitchen porter at “the big house”, as the villagers called it. He and Beryl had a good relationship, but he knew exactly where he stood. He was the nephew of Ruby Gedge, an old friend and colleague of Beryl, who had recently retired after many years in service at the Hall. She, therefore, felt that it was incumbent on her to keep an eye on young James, and to make sure that he stayed on the straight and narrow.

The trouble was that James was something of a dreamer and all he could think about was his fishing. He was a handsome young chap of eighteen years of age, medium height, and with blonde hair that always looked as though a comb had not passed through it for days. He was quiet and sensitive, and, despite his poor timekeeping, Beryl had found James to be a good worker.

James’ daily kitchen duties revolved around the serving of meals to the household, beginning the process by lighting the ovens when he arrived for work at 6.00am. He would be given a series of tasks by Beryl, which ran alongside serving breakfast and lunch, and the subsequent clearing down. After luncheon duties had been carried out, James would usually be permitted to leave the Hall for the afternoon.

So far, this Tuesday had been rather quiet, and he had finished his work quite early. It was a lovely, clear sunny day and James had spent his afternoon on the riverbank. Yet he had been expected to return to perform dinner duties at 4.00pm and had arrived back late. Again.

Beryl set him to work immediately.

‘James, go and see Mr Jenkins, will you? And ask him to find out whether his lordship wants to take his dinner in the dining room, or whether he is going to remain in his bedroom and take it up there.’

‘Yes, Mrs Aldis.’

‘And I suppose we’d better find out what our Mary Magdalene wants for her dinner.’

‘Yes, Mrs Aldis.’

He found Raymond Jenkins in the study, where he was replenishing the decanters. The butler advised him that Sister Margaret was in the garden, busy with her painting.

James made his way outside where he found the nun sitting in his lordship’s Bath chair, which was parked in front of the summerhouse. She was staring into the middle distance. Her easel had been erected and mounted on it was a half-completed landscape scene. Her palette and brushes were by her side. She was an attractive young woman for a nun, and James regarded her with a mixture of awe and admiration. He was reluctant to disturb her as he assumed that she must be thinking through some aspect of her artwork. She looked quite serene, and, although her feet were bare, she was fully clothed, wearing the habit, wimple and the large metal crucifix that he always found intimidating.

‘Excuse me, Sister, but I have been told by Mrs Aldis to find out what you’d like for dinner and whether you want to have your meal in the dining room.’

‘Where will his lordship be?’

‘I have an idea that his lordship might be dining alone in his bedroom, but I won’t know until Mr Jenkins has spoken to him.’

James considered the artwork. ‘That’s very good, Sister.’

Sister Margaret ignored his comment.

‘Nothing for me, can’t you see I’m busy?’ said the nun, in what James took to be a rather dismissive and brusque manner. She did not even turn her head to look in his direction.

James felt humiliated and was upset by her attitude. He said nothing further and decided to leave her to her painting. Why would she want to speak to me like that? he thought, as he walked away from her. He reminded himself that she didn’t really know him and so her response couldn’t have been personal, so James decided he wasn’t going to let it upset him. ‘Miserable, ignorant cow!’ he said to himself, as he walked back to the kitchen. James would have liked to have told her where to get off, but he knew he’d lose his job over it. He just walked back inside the kitchen.

Although the sister had been a guest at the Hall for several weeks, James had had little to do with her in that time. He was aware that other members of staff had formed the opinion that she was stern to the point of rudeness. They didn’t like her at all, and they all took the view that she was best avoided. He wondered how she had found herself taking holy orders to become a nun in the first place. It certainly didn’t suit her personality.

Ja

mes was still smarting from his encounter with the nun, but he made a conscious effort to replace thoughts of Sister Margaret with his plan to prebait a stretch of the river where, during the afternoon, he had seen a few nice chub. Back in the comfort of a dream, he just started to peel the potatoes, deep in thought.

‘Well?’ said Mrs Aldis.

‘Well what, Mrs Aldis?’

‘Well, what does she want for her dinner?’

‘She doesn’t want anything, Mrs Aldis.’

‘Really!’ she said, as she slapped a ball of dough down on the kitchen table and started kneading it, vigorously applying extra pressure.

‘She’s a strange one and no mistake. She hardly touched her lunch. We had to throw it away in the end. I really can’t stand to see perfectly good food going to waste, it’s criminal.’

‘Perhaps she’s fasting or maybe sickening for something.’

‘I don’t think so.’

‘Maybe she’s got worms.’

‘Don’t be rude, now, young man,’ said Mrs Aldis, giggling to herself.

James just carried on with his few remaining spuds. He was away again with the chub, anticipating that he would get an early night, and once away from the Hall he would be straight back down to the river to meet his friends.

*

‘I still can’t get off to sleep for any length of time, Adina.’

‘Perhaps you are worrying too much. Try to empty your mind and relax.’

‘I’ve tried. I seem to be able to go off for an hour or so, then my mind switches on and I start thinking.’

‘Would you like me to make a hot drink for you, my lord? Perhaps a mug of cocoa might help to calm you.’

‘No, thank you, Adina. It’s good of you, but that will just make me want to go to the lavatory.’

‘If that is all for now, my lord, may I go back to our apartment for a while to do some housework?’

Devotion to Murder

Devotion to Murder An Oik's Progress

An Oik's Progress